2.4 Involvement of migrant fishermen

There are two types of migrant fishers: those who migrate seasonally each year in search of fish and those who have already settled with their families for several generations in the destination village. In many cases, migrant fishers’ attention is focused on their home villages and they have a strong sense that their migration sites are temporary. Consequently, a “resource disposable’ mindset, whereby migrant fishers can simply move to another location once the local resources are depleted, tends to dominate their behavioural patterns. From this point of view, migrants who have established themselves at the migration site are positioned between local residents and seasonal migrants in terms of their awareness of local resources. Thus, the character and position of migrant fishermen and their relationship with the local population differ depending on the various social relationships in the locality. In this case, the migratory fishermen who settled in the migration area are positioned between local fishers and seasonal migrant fishers in their consciousness and are thus potential intermediaries.

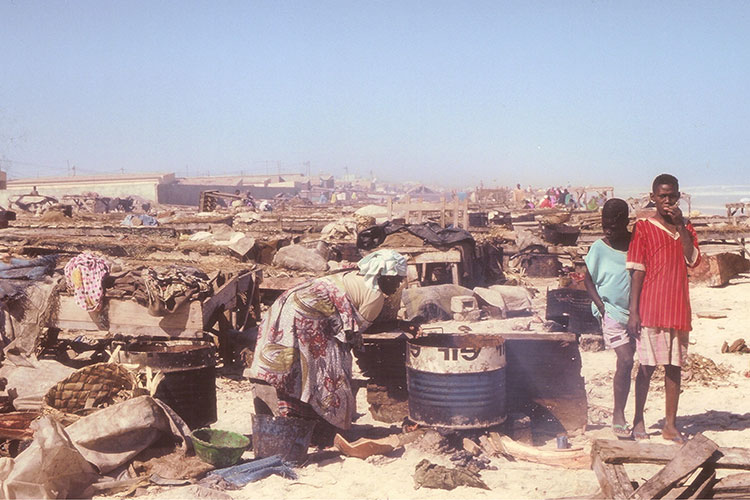

4. Migrant fishermen in Senegal

The fishermen of Saint-Louis, called Guet Ndariens, are the most famous seasonal migrant fishermen in Senegal. They travel seasonally to the coastal areas of Lompoul and Kayar on the Great Coast to fish. In the fishing ports near Dakar, where there is a high concentration of fishing enterprises, migrant fishermen travel from the surrounding localities in search of high prices for fish and some have settled there. Some places, such as Djifer in the southernmost part of the Petite Côte, which were originally strongholds of migrant fishermen, have been transformed into fishing villages by sedentarisation.

Many migrant fishers in Senegal feel that they are outsiders in the destination fishing villages and are therefore less likely to be actively involved in the resource management activities by the destination fishing villages. This causes problems when local fishers try to respect catch limits, which are not communicated to migrant fishers, leading to friction with local fishers. The strong sense of belonging to the village of origin and the lack of solidarity with the communities in the destination villages, as is the case for the fishermen in Djifer, also makes resource management activities difficult.

As fisheries resource management is only effective when all fishers who share fishing grounds and resources are involved, it is a major challenge for resource management in West Africa to understand the nature and position of migrant fishers as stakeholders and to consider how to involve them in resource management activities. The following are some of the ways in which local resource management organisations, in collaboration with such parties as the Directorate of Fisheries, local authorities, and donors, can involve migrant fishers in resource management activities.

- Invite representatives of migrant fishers as members of the resource management organisation

- Plan resource management activities in a participatory manner, including migrant fishers

- Take action to involve migrant fishers in the resource management

- Understand the effect of the inclusion of migrant fishers and improving measures

Invite representatives of migrant fishers as members of the resource management organisation.

‘Section 2.1 Establishment and strengthening of resource management organisations’ states that, to meet the challenges of fisheries resource management, the purpose, need, and role of the resource management organisation should be shared with the stakeholders and that the formation or restructuring of the resource management organisation should be discussed in a participatory manner. At this time, the participants in stakeholder meetings are often limited to representatives of fishing communities consisting of local people. At such meetings, people comment that ‘even if the village decides on resource management activities, the migrant fishers do not follow them’. There is a pattern of ‘sedentary’ versus ‘migrants’, which seems to imply an adversarial relationship. The first thing to do is to recognise that resource management activities are aimed at all users of the target resource and that if migrant fishers use the same resource and fishing grounds, then all users, including migrant fishers, should be the focus of the activities.

Thus, it is reasonable to include representatives of migrant fishers who have settled in the village and seasonal migrant fishers as members of the resource management organisation. It is important to reaffirm the problem of migratory fishermen in resource management activities as one of the issues to resolve by changing their attitudes towards mobile fishermen.

14. History of conflicts between fisheries on the Grand Côte

On the Grand Côte of Senegal, repeated conflicts between Kayar fishers and migrant Guet Ndariens have occurred because the Guet Ndariens use gillnets in waters designated by Kayar fishers as hand-line fishing areas. Establishing and legalising a specific method of designating fishing zones through discussions between the two parties would be one way to avoid conflict.

Plan resource management activities in a participatory manner, including for migrant fishers.

During the analysis of the current situation of migrant fishers and stakeholder analysis, issues such as the number of migrant fishers, types of fishing activities, timing of fishing activities, impact on resources, the feeling of migrant fishers towards resource management, and interests within the community are clarified and analysed. At this point, if the members of the resource management organisation include representatives of migrant fishers, it will be possible to obtain a more realistic picture of the activities, awareness, and positions of migrant fishers, and a better understanding of the fishing community as a whole.

When planning resource management activities in a participatory workshop with local residents, it is better to ensure that not only representatives of migrant fishers who are members of the resource management organisation are included but also representatives of other migrant fishers[1] (e.g. professional groups), so that all workshop participants understand that they are stakeholders using common resources and fishing grounds, and that there is an honest and open exchange of views and considered planning of resource management.

15. Changes in the practice of receiving migrant fishers in the delta in central Senegal

The activities of the beach committee introduced by the IUCN in the Saloum delta have required a change in the culture of welcoming strangers that the Saloum locality have developed for many years. Today, with a growing population and increased pressure for resource extraction, the question is how to avoid conflict and how to live in harmony with migrant fishermen in a contemporary context.

Take action to involve migrant fishers in the resource management.

If local resource management is not functioning because of migrant fishers from outside, it is necessary to consider measures to avoid conflicts between local and migrant fishers and implement fisheries resource management.

6. Initiatives of leading fishers for the inclusion of migrant fishermen

In Lompoul, Grand Cote, drift nets operated at night by migrant fishermen from neighbouring Saint-Louis and Fase Boye sometimes get entangled with the buoy lines of bottom gill nets set by local fishermen. The migrant fishers often cut the buoy lines at night, causing the loss of the drift nets of the local fishermen. In 2020, fishermen in Lompoul confiscated the drift nets of Fase Boye and Saint Luis fishermen, leading to a conflict. To resolve the conflict, leading fishers of CLPA Lompoul travelled to Saint-Louis and Fase Boye in early 2021 and later invited leading fishers of both locations to Lompoul to discuss drift net operations in Lompoul by migrant fishers. After coordination, an agreement was reached to prohibit nighttime operations of drift net fishing between 15 June and 15 July 2021, the peak fishing season for bottom gillnet fishing, and this was enacted as a Luga Provincial Ordinance.

7. Conflict resolution through innovative technology

CLPA Fase Boye consists of four communities: Fase Boye, Mboro, Lite, and Jogo. Fase Boye, Lite, and Jogo are active in drift-net fishing, while Mboro is active in bottom gillnet fishing. The difference in fishing practice is a source of conflict, as drift nets get entangled with bottom gill nets at night. The fishermen of CLPA Fase Boye have resolved the conflict by applying innovative technology. When considering how to solve problems in fishermen's conflicts, it is necessary to identify the nature of the problem first, and then examine the solution from different perspectives.

Understand the effects of the inclusion of migrant fishers and improving measures.

The Directorate of Fisheries, local authorities, and donors work with resource management organisations, whose members include local population leaders and migrant fishermen leaders, to monitor seasonal fluctuations in catch (fishing effort) due to fishermen’s movements, understand the effectiveness of resource management activities, and consider measures to further improve their effectiveness. One such measure is to make it compulsory to provisionally register fishing boats moving seasonally to their destination. Incentives for temporary registration can also be introduced, such as the inability to buy tax-free fuel without proof of temporary registration at the destination.

1. Depending on the situation and location, migrant fishers may constitute more than one social group. In this case, representatives from each social group of migrant fishers should be included in the workshop.